Items related to Tail-End Charlies: The Last Battles of the Bomber War,...

Toward the end of the conflict, too, they continued to sacrifice their lives to shatter an enemy sworn never to surrender. Blasted out of the sky in an instant or bailing out from burning aircraft to drop helplessly into hostile hands, they would die in their tens of thousands to ensure the enemy's defeat. Especially vulnerable were the "tail-end Charlies"---for the Americans, which meant two things: the gunners who flew countless missions in a plexiglass bubble at the back of the bomber, and the last bomber in the formation who ended up flying through the most hell, and for the British, the rear-gunners who flew operations in a Plexiglas bubble at the back of the bomber.

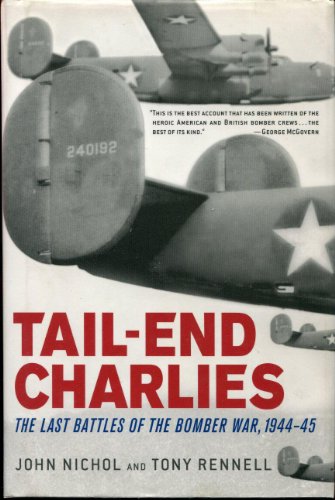

Following their groundbreaking revelations about the ordeals suffered by Allied prisoners of war in their bestselling book, The Last Escape, John Nichol and Tony Rennell tell the astonishing and deeply moving story of the controversial last battles in the skies of Germany through the eyes of the forgotten heroes who fought them. "This is the best account that has been written of the heroic American and British bomber crews . . . the best of its kind."

---George McGovern "Rivaling the best of Stephen Ambrose's work, Tail-End Charlies gives a breathtakingly intimate look at the lives, loves, and deaths of the brave airmen of the greatest generation. This fascinating book is as valuable for its stories of joyous life on the ground as it is for its sobering tales of death in the air. You see the whole picture of the war here from the eyes of the strong young men who fought it."

---Walter J. Boyne, bestselling author of Beyond the Wild Blue

"Adds new dimensions to the saga of the air war in Europe. The eyewitness accounts, reported within the context of the battle against Nazi Germany, provide a sense of the ordeals, the terror, the gore, and the heroism of ordinary men thrust into the savagery of aerial combat."

---Gerald Astor, author of The Mighty Eighth

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Tony Rennell is the co-author of The Last Escape and many other books. He is a regular contributor to British newspapers and, formerly,the former associate editor of The Sunday Times (London).

1IN THE FIRING LINE"The coldest, loneliest, most dangerous job of all."--RICHARD HOLMES, MILITARY HISTORIAN

SITTING IN THE COPILOT'S SEAT OF A B-17 FLYING FORTRESS NICKNAMED La-Dee-Doo, twenty-year-old Jim O'Connor from Chicago had plenty of time to contemplate his fate. It was not so very long since he had been at a desk in high school sweating for his English Lit exams. He still carried in his pack a relic of those days--a book called A Treasury of Great Poems--and he would seek solace in the inspirational words he found there before setting out on every mission. It seemed a lifetime ago now, but just a couple of months earlier, back in the United States, he had flung off his uniform, with its newly acquired pilot's wings and second lieutenant's bars, and reveled in a day of exceptional loveliness in a lush Oklahoma valley. A warm sun shone in a cloudless sky. "It was a rare moment of peace and beauty in our uprooted, uncertain and somewhat chaotic young lives," he later recalled. He swam in a lake and then soaked his head under a spectacular waterfall. Now he was on his way to a baptism of fire over Germany.As a member of the 388th Bomb Group based at Knettishall in eastern England, he was waiting to take up the "Tail-End Charlie" position, so often assigned to rookie crews like his, in a huge bomber formation. He knew that bringing up the rear of 700, 800, maybe 1,000 aircraft would leave him exposed to enemy fighters in search of an easy kill or to antiaircraft gunners on the ground who had finally got their range. The experience thatday would be imprinted on O'Connor's mind for the rest of his life. It had begun, as it always did, with a midnight awakening.The duty sergeant, a big pleasant former gunner from North Carolina, quietly entered the barracks and shone a flashlight on a roster in his hand. He spoke softly as he aimed the flashlight beam into the face of each crew member scheduled to fly that day. "Lootenant, wake up. You all are flying today." He slowly worked his way the length of the hut, skipping a relieved crew here and there who were getting the day off. He finally arrived at our corner, and we were up, into our long underwear, woolen uniforms, flight suits, and A-2 leather jackets in a couple of minutes. After breakfast we loaded into GI trucks which raced through the darkness and disgorged us in front of the briefing room. Thirty-six crews--360 airmen plus a few intelligence, weather, and auxiliary officers--looked up at a stage containing a covered wall-size map of England and northern Europe. Our target that day was a deep-penetration one--a heavily defended factory at Schweinfurt producing most of the ball bearings for the entire German military. A groan went up when it was announced.The briefing would end with the synchronizing of watches at around 3:00 A.M. Each crew member then had a particular duty to perform. As the copilot, mine was to pick up the crew's parachutes and escape kits from stores. Meanwhile, the Catholics in our ranks went off to a makeshift chapel on the flight line where the chaplain administered the sacraments and gave a farewell blessing. The Protestant and Jewish fliers had similar arrangements. After the tasks were all completed and the ship checked over, there was usually a wait of a half hour or more before takeoff time. The crew gathered around the stove in the ground-crew tent and either dozed off on the cots or had a last smoke. Everyone was alone with his own thoughts.1At 4:00 A.M., as the first streaks of dawn began to appear in the eastern sky, a green flare shot up from the control tower giving the signal to start engines. A tremendous roar shattered the peace of the night as 134 powerful 1,200 horsepower engines sprang into life. Then a second flare shot skyward and the aircraft began the taxi out toward the runway. In La-Dee-Doo, O'Connor and his crew followed the other heavily laden shipswaddling up to takeoff position. After the magnetos were checked and tail wheel locked, the skipper offered a final comforting glance to his crew as the engineer rammed the throttles full forward. The skipper gave the final nod and the brakes were released.We roared down the runway. The excitement of that moment of takeoff never diminished. It took some two hours for the entire force to form over England. We would fly in a big lazy climbing circle until the last ship, squadron, group, and wing were in position in the bomber stream. That day we were in the last wing (100-plus ships), the last group (36), the last squadron (12) and the last element (3), flying in so-called Purple Heart Corner, the most vulnerable position in the formation. Out of the hundreds of bombers hitting Schweinfurt, we would be the very last one over the target. We headed out over the North Sea toward the continent and climbed to altitude. The gunners practiced firing their guns. At 10,000 feet we went on oxygen and put on steel flak helmets. Every ten minutes or so we had an oxygen check, with each crew member reporting in to the copilot.Over the target, the sky was black with flak, the worst we had ever seen. And being at the tail end of the bomber stream, the German gunners by then had the exact range. Bursts of flak were exploding right below and around our ship, bouncing it up and down and sending jagged pieces of shrapnel through the fuselage. Our usually unexcitable tail gunner got on the intercom and yelled out, "Lieutenant, de flak is right on us. Let's get de hell out of heah!" The flak was so devastating that immediately after bombs away, the group leader made an abrupt forty-five-degree right diving turn off the target to get out of the range of gunfire. Being the last ship on the outside of the formation, the speed and angle of turn was greatly exaggerated for us.The plane was practically standing on its wing at a ninety-degree angle to the ground as the air speed rapidly increased. The skipper could not see anything from his seat, so I had to take over control and fly the plane myself on my own. By now there was both a gray undercast and a gray overcast, absolutely nothing visible by which I could gauge our flight attitude. Vertigo gripped me. I lost all balance and perspective. All I had to hang on to was the aircraft alongside--which meant that if she was heading for the ground then so were we. Eventually the group stabilized, and we rejoined the mainstream for the long haul home. The crew startedbreathing again and assessed the battle damage. The flak had taken out rudder and trim cables, and put more than twenty large holes in the side. The tail gunner and radio operator had near misses and the navigator was grazed by a piece of flak that tore his flight jacket and pierced his equipment bag.Just before 1:00 P.M. we landed back at base. As the wheels touched down, we were about to let out a collective sigh of relief, when the ship began to vibrate and bounce. A tire had been shot out. The skipper yelled at me to unlock the tail wheel. He then gunned the engines, pulling the ship off the runway into the muddy infield, thus keeping the landing strip clear for the other incoming aircraft, many with battle damage or wounded on board. That day only thirty-two out of the thirty-six aircraft that had taken off for battle from our base returned. As the skipper cut the engines, we sat there for some moments completely whacked out until a truck came out to pick us up. At debriefing, we felt we had earned the shot of bourbon which was waiting for us.O'Connor and his crew had survived their first experience as Tail-End Charlies and their first encounters on Purple Heart Corner, but four bombers from his group, along with forty of his comrades, had not. It had been every bit as bad as they feared, and they hoped to be spared a second experience. But a few weeks later they were rostered in the same position for a thousand-bomber raid on "the Big B," Berlin. "When the target was announced, a spontaneous groan erupted from the assembled bomber crews. I looked round the room and knew several crews would probably not make it back." He felt sure his would be one of them. Not only were they Tail-End Charlies again, they had also been assigned an older, patched-up B-17 for the trip, one that creaked and groaned as they rose into the morning sun. O'Connor felt like a medieval knight heading into battle, "knowing that the ultimate gamble was at hand, the throw of the dice that would determine life or death." That day death came very close. From his cockpit, O'Connor watched the Fortress next to his in the formation explode, its oxygen tanks hit by the same flak that had put a handful of harmless holes in his own aircraft. He and his men made it home. The other crew went on the list of 250 men missing that day. "How sweet it was to be alive!" O'Connor later wrote in his diary.Life for others in the Tail-End Charlie position was not so sweet andmany could not escape disaster. On a deep-penetration haul to the Leuna oil refinery, a B-17 named Knockout was in the last group of the thousand-plane formation, with navigator Dean Whitaker, lying in the nose cone, straining his eyes to catch sight of the full might of the Eighth Air Force ahead as it went in for the kill. What he saw was a huge black cloud--the flak from hundreds of 88mm guns, so many he thought the Germans must have moved every gun they had to protect their valuable oil supplies. He could see B-17s spiraling out of that cloud, some on fire, others missing a wing or tail. "Knowing it would soon be our turn to run the gauntlet made my blood pressure rise." If that was happening to the vanguard, what chance did those in the rear have?They slowed to one hundred and fifty miles an hour for the bomb run, and to Whitaker it felt as if they had come almost to a stop. "Flak was to the right, left, overhead, ahead, sometimes so close you could hear the dull thud of it exploding. I smelt burning metal and knew we had been hit. A shell exploding directly in front of us sent bits of steel through the nose." Bombs gone, and they wheeled away, out of the black cloud and into clear blue sky. The relief was momentary. "Bandits" came a cry over the intercom, and they were being chased by enemy fighters. "All hell broke loose. Our tail must have been shot off because the plane was going every way but straight." The rear gunner was dead. The aircraft began to nosedive, the stick and wheel useless in the pilot's hands. All that was left to do was lower the landing gear, a sign of surrender to the Germans, and jump.More than half the crew of Knockout parachuted straight into enemy hands. Surrounded by German troops the moment they landed, evasion was never an option. A dozen other planes had been hit, too, on that mission and altogether fifty bedraggled American airmen held up their hands in surrender that day and went into captivity. They at least were safe. Four others from the crew of Knockout were not, the pilot Herb Newman among them. Winds had swept them in a different direction and they drifted down near a small village, whose police chief enlisted the help of other Nazi thugs to slaughter them on the spot.2

While "Tail-End Charlie" in the American Eighth Air Force referred to the last aircraft in a formation, it had a different meaning to the men of Bomber Command, where it was RAF speak for the rear gunners. And British Tail-End Charlies were considered just as vulnerable as their Americannamesakes. Isolated and alone in the rear of his aircraft, nineteen-year-old RAF Sergeant Bob Pierson could testify to that.Unlike the Americans, who bombed in daylight hours, the British raids were launched at night, and so the red beacon shining in the darkening sky behind him was always his last sight of home. He sat with his back to the four engines of the Lancaster bomber, tucked into a space the size of a dustbin, and wondered, as he did every time, if he would ever see its glow again. Just ninety seconds earlier, as the Lancaster had turned on the taxiway and stood on full throttle, building up power before the pilot let off the brakes, Pierson, the rear gunner, had strained to see through the gloom of early evening. Yes, they were there--the adjutant, the ground crew, too, and lots of WAAFs, the RAF girls whose voices he would hope to hear from the control tower guiding them home to land in, what, eight and a half, nine hours' time. They were huddled round a small trailer, mugs of tea in one hand, all waving. Goodbye! Good luck! Charging down the runway, the Lancaster's rear wheel was first off the ground, and just before the front wheels lifted into flight the plane gave an involuntary "wag" of its tail. Pierson always felt it was as if the aircraft was waving goodbye to the well-wishers.The bomber, with seven tons of explosives in its belly for a night-time raid on Germany, rose slowly, turned left, and climbed in circles to join the formation assembling in the sky over the Lincolnshire countryside. Pierson, gazing back from the coffinlike rear turret at the now-receding red light on a farm cottage at the end of the runway, reflected on how important it was to get a proper send-off, that people should be there to see them go. "It gave me a sense of hope and of support," he recalled sixty years later. If the padre was there, it was an extra blessing. "I took quite a lot of comfort from him before each op. You could talk to him about your feelings, about being scared. He would help you put aside the fear of dying."3Once the war machine began to roll, that fear was unspoken, though it was a fellow traveler for all but the most devil-may-care airmen or the rawest recruits. Pierson remembered his very first operation over enemy territory, when he was overwhelmed by sheer excitement. "I felt just like a racing driver--not scared at all." Now experience had taught him what to expect and his mood was somber.The strict preoperation routine helped to calm the nerves. He had written his last letters to his loved ones before the lorry--"the blood wagon," they called it, with typically ghoulish RAF humor--had come to pick up him and his crew from their hut to take them to their plane. The letterswould be found in his locker if he didn't come back, one for his parents in north London, the other for Joyce, the girl he wished was his wife. Thoughts of her went through his mind as he stood on the edge of the airfield, waiting for the jeep to come racing along the perimeter track with the order to board the bomber. This was anxious time to kill. Some of the seven-man crews went through elaborate good-luck rituals. There would be banter and even songs. One navigator always crooned his way through "As Time Goes By" from Casablanca, the gritty Humphrey Bogart film they had all seen and loved on its recent release.4 "A fight for love or glory, a case of do or die ..." seemed appropriate for what lay ahead. Others would line up to urinate ceremonially against one of the Lancaster's huge front wheels, for good fortune or simply to empty their bladders before the long confinement. But Pierson's crew was a less boisterous bunch. "We tended to retreat into our own corners," he recalled. "The others were usually quiet, just sitting and thinking, but I liked to talk, probably because I was going to be on my own for the whole of the flight ahead."Once tucked up in his turret at the rear of the plane, he would not move for the entire trip. He would be alone, almost in his own private war. The others--pilot, flight engineer, navigator, ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherThomas Dunne Books

- Publication date2006

- ISBN 10 0312349874

- ISBN 13 9780312349875

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages432

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Tail-End Charlies: The Last Battles of the Bomber War, 1944--45

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. 1.65. Seller Inventory # 0312349874-2-1

Tail-End Charlies: The Last Battles of the Bomber War, 1944--45

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 1.65. Seller Inventory # 353-0312349874-new

Tail-End Charlies: The Last Battles of the Bomber War, 1944--45

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: NEW CONDITION. Dust Jacket Condition: NEW DUST JACKET. First Edition, First Printing. //NO REMAINDER MARK//NO PREVIOUS OWNER MARKS OF ANY KIND (no names or inscriptions, no bookplate, no underlining, etc) //NOT PRICECLIPPED// NEW MYLAR COVER//. Seller Inventory # 925

Tail-End Charlies: The Last Battles of the Bomber War, 1944--45

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: Brand New. 420 pages. 9.25x6.25x1.00 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # 0312349874

TAIL-END CHARLIES: THE LAST BATT

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.65. Seller Inventory # Q-0312349874