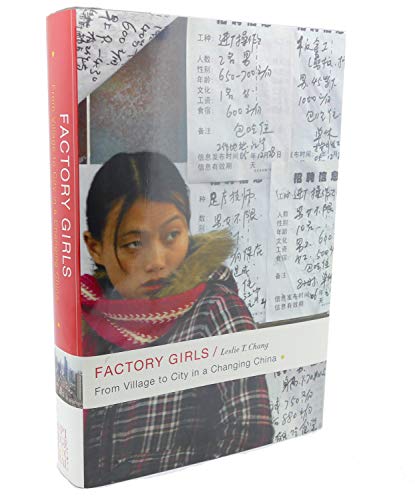

Items related to Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China

An eye-opening and previously untold story, Factory Girls is the first look into the everyday lives of the migrant factory population in China.

China has 130 million migrant workers—the largest migration in human history. In Factory Girls, Leslie T. Chang, a former correspondent for the Wall Street Journal in Beijing, tells the story of these workers primarily through the lives of two young women, whom she follows over the course of three years as they attempt to rise from the assembly lines of Dongguan, an industrial city in China’s Pearl River Delta.

As she tracks their lives, Chang paints a never-before-seen picture of migrant life—a world where nearly everyone is under thirty; where you can lose your boyfriend and your friends with the loss of a mobile phone; where a few computer or English lessons can catapult you into a completely different social class. Chang takes us inside a sneaker factory so large that it has its own hospital, movie theater, and fire department; to posh karaoke bars that are fronts for prostitution; to makeshift English classes where students shave their heads in monklike devotion and sit day after day in front of machines watching English words flash by; and back to a farming village for the Chinese New Year, revealing the poverty and idleness of rural life that drive young girls to leave home in the first place. Throughout this riveting portrait, Chang also interweaves the story of her own family’s migrations, within China and to the West, providing historical and personal frames of reference for her investigation.

A book of global significance that provides new insight into China, Factory Girls demonstrates how the mass movement from rural villages to cities is remaking individual lives and transforming Chinese society, much as immigration to America’s shores remade our own country a century ago.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Leslie T. Chang lived in China for a decade as a correspondent for the Wall Street Journal. She is married to Peter Hessler, who also writes about China. She lives in Colorado.

When you met a girl from another factory, you quickly took her measure. What year are you? you asked each other, as if speaking not of human beings but of the makes of cars. How much a month? Including room and board? How much for overtime? Then you might ask what province she was from. You never asked her name.

To have a true friend inside the factory was not easy. Girls slept twelve to a room, and in the tight confines of the dorm it was better to keep your secrets. Some girls joined the factory with borrowed ID cards and never told anyone their real names. Some spoke only to those from their home provinces, but that had risks: Gossip traveled quickly from factory to village, and when you went home every auntie and granny would know how much you made and how much you saved and whether you went out with boys.

When you did make a friend, you did everything for her. If a friend quit her job and had nowhere to stay, you shared your bunk despite the risk of a ten-yuan fine, about $1.25, if you got caught. If she worked far away, you would get up early on a rare day off and ride hours on the bus, and at the other end your friend would take leave from work--this time, the fine one hundred yuan--to spend the day with you. You might stay at a factory you didn't like, or quit one you did, because a friend asked you to. Friends wrote letters every week, although the girls who had been out longer considered that childish. They sent messages by mobile phone instead.

Friends fell out often because life was changing so fast. The easiest thing in the world was to lose touch with someone.

The best day of the month was payday. But in a way it was the worst day, too. After you had worked hard for so long, it was infuriating to see how much money had been docked for silly things: being a few minutes late one morning, or taking a half day off for feeling sick, or having to pay extra when the winter uniforms switched to summer ones. On payday, everyone crowded the post office to wire money to their families. Girls who had just come out from home were crazy about sending money back, but the ones who had been out longer laughed at them. Some girls set up savings accounts for themselves, especially if they already had boyfriends. Everyone knew which girls were the best savers and how many thousands they had saved. Everyone knew the worst savers, too, with their lip gloss and silver mobile phones and heart-shaped lockets and their many pairs of high-heeled shoes.

The girls talked constantly of leaving. Workers were required to stay six months, and even then permission to quit was not always granted. The factory held the first two months of every worker's pay; leaving without approval meant losing that money and starting all over somewhere else. That was a fact of factory life you couldn't know from the outside: Getting into a factory was easy. The hard part was getting out.

The only way to find a better job was to quit the one you had. Interviews took time away from work, and a new hire was expected to start right away. Leaving a job was also the best guarantee of getting a new one: The pressing need for a place to eat and sleep was incentive to find work fast. Girls often quit a factory in groups, finding courage in numbers and pledging to join a new factory together, although that usually turned out to be impossible. The easiest thing in the world was to lose touch with someone.

* * *

For a long time Lu Qingmin was alone. Her older sister worked at a factory in Shenzhen, a booming industrial city an hour away by bus. Her friends from home were scattered at factories up and down China's coast, but Min, as her friends called her, was not in touch with them. It was a matter of pride: Because she didn't like the place she was working, she didn't tell anyone where she was. She simply dropped out of sight.

Her factory's name was Carrin Electronics. The Hong Kong-owned company made alarm clocks, calculators, and electronic calendars that displayed the time of day in cities around the world. The factory had looked respectable when Min came for an interview in March 2003: tile buildings, a cement yard, a metal accordion gate that folded shut. It wasn't until she was hired that she was allowed inside. Workers slept twelve to a room in bunks crowded near the toilets; the rooms were dirty and they smelled bad. The food in the canteen was bad, too: A meal consisted of rice, one meat or vegetable dish, and soup, and the soup was watery.

A day on the assembly line stretched from eight in the morning until midnight--thirteen hours on the job plus two breaks for meals--and workers labored every day for weeks on end. Sometimes on a Saturday afternoon they had no overtime, which was their only break. The workers made four hundred yuan a month--the equivalent of fifty dollars--and close to double that with overtime, but the pay was often late. The factory employed a thousand people, mostly women, either teenagers just out from home or married women already past thirty. You could judge the quality of the workplace by who was missing: young women in their twenties, the elite of the factory world. When Min imagined sitting on the assembly line every day for the next ten years, she was filled with dread. She was sixteen years old.

From the moment she entered the factory she wanted to leave, but she pledged to stick it out six months. It would be good to toughen herself up, and her options were limited for now. The legal working age was eighteen, though sixteen- and seventeen-year-olds could work certain jobs for shorter hours. Generally only an employer that freely broke the labor law--"the very blackest factories," Min called them--would hire someone as young as she was.

Her first week on the job, Min turned seventeen. She took a half day off and walked the streets alone, buying some sweets and eating them by herself. She had no idea what people did for fun. Before she had come to the city, she had only a vague notion of what a factory was; dimly, she imagined it as a lively social gathering. "I thought it would be fun to work on the assembly line," she said later. "I thought it would be a lot of people working together, busy, talking, and having fun. I thought it would be very free. But it was not that way at all."

Talking on the job was forbidden and carried a five-yuan fine. Bathroom breaks were limited to ten minutes and required a sign-up list. Min worked in quality control, checking the electronic gadgets as they moved past on the assembly line to make sure buttons worked and plastic pieces joined and batteries hooked up as they should. She was not a model worker. She chattered constantly and sang with the other women on the line. Sitting still made her feel trapped, like a bird in a cage, so she frequently ran to the bathroom just to look out the window at the green mountains that reminded her of home. Dongguan was a factory city set in the lush subtropics, and sometimes it seemed that Min was the only one who noticed. Because of her, the factory passed a rule that limited workers to one bathroom break every four hours; the penalty for violators was five yuan.

After six months Min went to her boss, a man in his twenties, and said she wanted to leave. He refused.

"Your performance on the assembly line is not good," said Min's boss. "Are you blind?"

"Even if I were blind," Min countered, "I would not work under such an ungrateful person as you."

She walked off the line the next day in protest, an act that brought a hundred-yuan fine. The following day, she went to her boss and asked again to leave. His response surprised her: Stay through the lunar new year holiday, which was six months away, and she could quit with the two months' back pay that the factory owed her. Min's boss was gambling that she would stay. Workers flood factory towns like Dongguan after the new year, and competition for jobs then is the toughest.

After the fight, Min's boss became nicer to her. He urged her several times to consider staying; there was even talk of a promotion to factory-floor clerk, though it would not bring an increase in pay. Min resisted. "Your factory is not worth wasting my whole youth here," she told her boss. She signed up for a computer class at a nearby commercial school. When there wasn't an overtime shift, she skipped dinner and took a few hours of lessons in how to type on a keyboard or fill out forms by computer. Most of the factory girls believed they were so poorly educated that taking a class wouldn't help, but Min was different. "Learning is better than not learning," she reasoned.

She phoned home and said she was thinking of quitting her job. Her parents, who farmed a small plot of land and had three younger children still in school, advised against it. "You always want to jump from this place to that place," her father said. Girls should not be so flighty. Stay in one place and save some money, he told her.

Min suspected this was not the best advice. "Don't worry about me," she told her father. "I can take care of myself."

She had two true friends in the factory now, Liang Rong and Huang Jiao'e, who were both a year older than Min. They washed Min's clothes for her on the nights she went to class. Laundry was a constant chore because the workers had only a few changes of clothes. In the humid dark nights after the workday ended, long lines of girls filed back and forth from the dormitory bathrooms carrying buckets of water.

Once you had friends, life in the factory could be fun. On rare evenings off, the three girls would skip dinner and go roller-skating, then return to watch a late movie at the factory. As autumn turned into winter, the cold in the unheated dorms kept the girls awake at night. Min dragged her friends into the yard to play badminton until they were warm enough to fall asleep.

The 2004 lunar new year fell in late January. Workers got only four days off, not enough t...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSpiegel & Grau

- Publication date2008

- ISBN 10 0385520174

- ISBN 13 9780385520171

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages432

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0385520174

Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0385520174

Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0385520174

Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0385520174

Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0385520174

Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Dust Jacket Condition: New. 1st Edition. First Edition stated, First Printing with correct number line sequence, no writing, marks, underlining, or bookplates. No remainder marks. Spine is tight and crisp. Boards are flat and true and the corners are square. Dust jacket is not price-clipped. This collectible, " NEW" condition first edition/first printing copy is protected with a polyester archival dust jacket cover. Beautiful collectible copy. Unread. Pristine. GIFT QUALITY. Seller Inventory # 007571

Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: Brand New. 432 pages. 10.25x6.50x1.50 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # 0385520174

Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon0385520174

Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks91602

Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.6. Seller Inventory # Q-0385520174