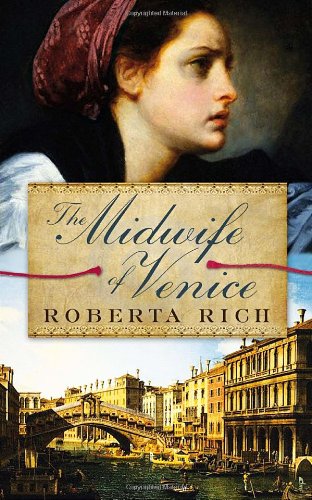

Items related to The Midwife of Venice

At midnight, the dogs, cats, and rats rule Venice. The Ponte di Ghetto Nuovo, the bridge that leads to the ghetto, trembles under the weight of sacks of rotting vegetables, rancid fat, and vermin. Shapeless matter, perhaps animal, floats to the surface of Rio di San Girolamo and hovers on its greasy waters. Through the mist rising from the canal the cries and grunts of foraging pigs echo. Seeping refuse on the streets renders the pavement slick and the walking treacherous.

It was on such a night that the men came for Hannah.

—

Hannah Levi is known throughout sixteenth-century Venice for her skill in midwifery. When a Christian count appears at Hannah's door in the Jewish ghetto imploring her to attend his labouring wife, who is nearing death, Hannah is forced to make a dangerous decision. Not only is it illegal for Jews to render medical treatment to Christians, it's also punishable by torture and death. Moreover, as her Rabbi angrily points out, if the mother or child should die, the entire ghetto population will be in peril.

But Hannah’s compassion for another woman’s misery overrides her concern for self-preservation. The Rabbi once forced her to withhold care from her shunned sister, Jessica, with terrible consequences. Hannah cannot turn away from a labouring woman again. Moreover, she cannot turn down the enormous fee offered by the Conte. Despite the Rabbi’s protests, she knows that this money can release her husband, Isaac, a merchant who was recently taken captive on Malta as a slave. There is nothing Hannah wants more than to see the handsome face of the loving man who married her despite her lack of dowry, and who continues to love her despite her barrenness. She must save Isaac.

Meanwhile, far away in Malta, Isaac is worried about Hannah’s safety, having heard tales of the terrifying plague ravaging Venice. But his own life is in terrible danger. He is auctioned as a slave to the head of the local convent, Sister Assunta, who is bent on converting him to Christianity. When he won’t give up his faith, he’s traded to the brutish lout Joseph, who is renowned for working his slaves to death. Isaac soon learns that Joseph is heartsick over a local beauty who won’t give him the time of day. Isaac uses his gifts of literacy and a poetic imagination—not to mention long-pent-up desire—to earn his day-to-day survival by penning love letters on behalf of his captor and a paying illiterate public.

Back in Venice, Hannah packs her “"birthing spoons”—secret rudimentary forceps she invented to help with difficult births—and sets off with the Conte and his treacherous brother. Can she save the mother? Can she save the baby, on whose tiny shoulders the Conte’s legacy rests? And can she also save herself, and Isaac, and their own hopes for a future, without endangering the lives of everyone in the ghetto?

The Midwife of Venice is a gripping historical page-turner, enthralling readers with its suspenseful action and vivid depiction of life in sixteenth-century Venice. Roberta Rich has created a wonderful heroine in Hannah Levi, a lioness who will fight for the survival of the man she loves, and the women and babies she is duty-bound to protect, carrying with her the best of humanity’s compassion and courage.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Born in Buffalo, New York, Roberta Rich was until recently a lawyer practicing family law. She has also been a student, waitress, nurses’ aide, hospital admitting clerk, and factory assembly line worker. She currently divides her time between Vancouver, B.C. and Colima, Mexico. She is married and has one daughter, three step-children, a German Shepherd, tropical fish and many oversexed parakeets. The Midwife of Venice marks her debut as a novelist.

“Much of the history of women is written in water,” says Rich of the impetus to create a literary heroine based on the history of the Jews in Venice, after touring the Venice ghetto on holiday. “Their accomplishments disappear as smoothly as a stone thrown in a pond. The creations of women are transitory — meals cooked, clothes mended, clothes washed, clothes sold (for one of the few professions Jews were permitted at the time was trade in second hand clothing), children born, children birthed, and children raised. After that trip, I started to read all I could find on the subject of daily life in the ghetto. There is precious little. And precious little about the daily lives of women in particular and how they gave birth. This book is a way to imagine a way into all that invisible history.”

Ghetto Nuovo, Venice

1575

At midnight, the dogs, cats, and rats rule Venice. The Ponte di Ghetto Nuovo, the bridge that leads to the ghetto, trembles under the weight of sacks of rotting vegetables, rancid fat, and vermin. Shapeless matter, perhaps animal, floats to the surface of Rio di San Girolamo and hovers on its greasy waters. Through the mist rising from the canal the cries and grunts of foraging pigs echo. Seeping refuse on the streets renders the pavement slick and the walking treacherous.

It was on such a night that the men came for Hannah. She heard their voices, parted the curtains, and tried to peer down into the campo below. Without the charcoal brazier heating her room, thick ice had encrusted the inside of the window and obscured her view. Warming two coins on her tongue, grimacing from the bitter metallic taste, she pressed them to the glass with her thumbs until they melted a pair of eyeholes through which she could stare. Two figures, three storeys below, argued with Vicente, whose job it was to lock the gates of the Ghetto Nuovo at sunset and unlock them at sunrise. For a scudo, he guided men to Hannah’s dwelling. This time, Vicente seemed to be arguing with the two men, shaking his head, emphasizing his words by waving about a pine torch, which cast flickering light on their faces.

Men often called for her late at night—it was the nature of her profession—but these men were out of place in the ghetto in a way she could not immediately put into words. Stealing a look through the protection of the eyeholes, she saw that one was tall, barrel-chested, and wore a cloak trimmed with fur. The other was shorter, stouter, and dressed in breeches of a silk far too thin for the chill of the night air. The lace on the tall man’s cuff fluttered like a preening dove as he gestured toward her building.

Even through the window, she could hear him say her name in the back of his throat, the h in Hannah like ch, sounding like an Ashkenazi Jew. His voice ricocheted off the narrow, knife-shaped ghetto buildings that surrounded the campo. But something was wrong. It took her a moment to realize what was odd about the two strangers.

They wore black hats. All Jews, by order of the Council of Ten, were obliged to wear the scarlet berete, to symbolize Christ’s blood shed by the Jews. These Christians had no right to be in the ghetto at midnight, no reason to seek her services.

But maybe she was too quick to judge. Perhaps they sought her for a different purpose altogether. Possibly they brought news of her husband. Perhaps, may God be listening, they had come to tell her that Isaac lived and was on his way home to her.

Months ago, when the Rabbi informed her of Isaac’s capture, she was standing in the same spot where these men stood now, near the wellhead, drawing water for washing laundry. She had fainted then, the oak bucket dropping from her arms onto her shoe. Water soaked the front of her dress and cascaded onto the paving stones. Her friend Rebekkah, standing next to her under the shade of the pomegranate tree, had caught Hannah by the arm before she struck her head on the wellhead. Such had been her grief that not until several days later did she realize her foot was broken.

The men moved closer. They stood beneath her window, shivering in the winter cold. In Hannah’s loghetto, dampness stained the walls and ceiling grey-brown. The coverlet that she had snatched from the bed and wrapped around her shoulders to keep out the chill of the night clung to her, holding her in a soggy embrace. She hiked it higher around her, the material heavy with her nightmares, traces of Isaac’s scent, and oil from the skins of oranges. He had been fond of eating oranges in bed, feeding her sections as they chatted. She had not washed the blanket since Isaac had departed for the Levant to trade spices. One night he would return, steal into their bed, wrap his arms around her, and again call her his little bird. Until then, she would keep to her side of the bed, waiting.

She slipped on her loose-fitting cioppą with the economical movements of a woman accustomed to getting ready in haste, replaced the coverlet over her bed, and smoothed it as though Isaac still slumbered beneath.

While she waited for the thud of footsteps and the blows on the door, she lit the charcoal brazier, her fingers so awkward with cold and nervousness that she had difficulty striking the flint against the tinder box. The fire smouldered, then flared and burned, warming the room until she could no longer see clouds of her breath in the still air. From the other side of the wall, she heard the gentle snoring of her neighbours and their four children.

Peering through the eyeholes, now melting from the heat of her body, she stared. The tall man, his voice strident, pivoted on his heel and strode toward her building; the stout man trotted behind, managing two steps for each one of the tall man’s. She held her breath and willed Vicente to tell them what they wanted of her was impossible.

To soothe herself, she stroked her stomach, hating the flatness of it, feeling the delicate jab of her pelvic bones through her nightdress. She felt slightly nauseated and for a joyful moment experienced a flicker of hope, almost like the quickening of a child. But it was the smell of the chamber pot and the mildew of the walls playing havoc with her stomach, not pregnancy. She was experiencing her courses now, and would purify herself next week in the mikvah, the ritual bath that would remove all traces of blood.

Soon she felt vibrations on the rickety stairs and heard mumbled voices approaching her door. Hannah wrapped her arms around herself, straining to hear. They called her name as they pounded on the door, which made her want to dive into bed, pull the covers over her head, and lie rigid. From the other side of the wall, her neighbour, who had delivered twins last year and needed her rest, rapped for quiet.

Hannah twisted her black hair into a knot at the back of her head, secured it with a hairpin. Before they could burst through the entrance, she flung open the door, about to shout to Vicente for assistance. But her hand flew to her mouth, stifling a cry of surprise. Between the two Christian men, pale as a scrap of parchment, stood the Rabbi. Hannah backed into her room.

Rabbi Ibraiham kissed his figers and reached up to touch the mezzuzah, the tiny box containing Scripture fastened to the right-hand side of her door jamb. “Shalom Aleichem and forgive us, Hannah, for disturbing you.” The Rabbi had dressed in haste; the fringe of his prayer shawl dangled unevenly around his knees, his yarmulke askew. “Aleichem shalom,” she replied. She started to put a hand on the Rabbi’s arm but stopped herself just in time. A woman was not to touch a man outside of her family, even when not having her monthly flow.

“These men need to talk with you. May we come in?”

Hannah averted her eyes as she always did in the presence of a man other than Isaac. They should not enter. She was not properly dressed; her room could not contain all four of them.

In a voice pitched higher than normal, she asked the Rabbi, “Your wife is better? I heard she was suffering from the gout and has been in bed since last Shabbat.”

The Rabbi was stooped, his clothes redolent with the fusty odour of a man lacking a healthy wife to air them and ensure he did not sit hunched all night reading over beeswax candles. Perhaps, Hannah thought, Rivkah had finally gone to the Jewish quarter in Rome to live with their eldest son, as she had often threatened.

The Rabbi shrugged. “Rivkah’s hands and feet remain immobile, but, alas, not her tongue. Her words remain as cutting as a sword.”

“I’m sorry to hear that.”

The Rabbi’s marital troubles were not a secret from anyone in the ghetto within earshot of their apartment. He and Rivkah had not enjoyed a peaceful moment in their forty years together.

“Gentlemen, this is our midwife, Hannah. May she be blessed above all women.” The Rabbi bowed. “Hannah, this is Conte Paolo di Padovani and his brother Jacopo. May God his rock protect them and grant them long life. The Conte insisted that I bring him to you. He asks for our help.” Our help? Hannah thought. Did she deliver sermons?

Did the Rabbi deliver babies?

“But as I have explained to the Conte,” said the Rabbi, “what he asks is not possible. You are not permitted to assist Christian women in childbirth.”

Only last Sunday in the Piazza San Marco, Fra Bartolome, the Dominican priest, had railed against Christians receiving medical treatment from Jews, or as he phrased it, “from enemies of the Cross.”

The Conte tried to interrupt, but the Rabbi held up a finger. “Papal dispensation, you are going to tell me? Not for a humble midwife like Hannah.”

This time it seemed the Rabbi was on Hannah’s side. They had common cause in refusing the Conte’s request.

The Conte looked to be in his fifties, at least twice Hannah’s age. Fatigue showed in his hollowed cheeks, making him appear as old as the Rabbi. His brother, perhaps ten years younger, was soft and not as well made, with sloping shoulders and narrow chest. The Conte nodded at her and pushed past the Rabbi into the room, ducking his head to avoid scraping it on the slanted ceiling. He was large, in the fashion of Christians, and florid from eating roasted meats. Hannah tried to slow her breathing. There seemed to be not enough air in the room for all of them.

“I am honoured to meet you,” he said, removing his black hat. His voice was deep and pleasant, and he spoke the sibilant Veneziano dialect of the city.

Jacopo, his brother, was immaculate, his chubby cheeks well powdered, not a spot of mud disgracing his breeches. He entered warily, placing one foot ahead of the other as though he expected the creaky floor to give way under him. He made a half bow to Hannah.

The Conte unfastened his cloak and glanced around her loghetto, taking in the trestle bed, the stained walls, the pine table, and the menorah. The stub of a beeswax candle in the corner guttered, casting shadows around the small room. Clearly, he had never been inside such a modest dwelling, and judging by his stiff posture and the way he held himself away from the walls, he was not comfortable being in one now.

“What brings you here tonight?” Hannah asked, although she knew full well. The Rabbi should not have led the men to her home. He should have persuaded them to leave. There was nothing she could do for them.

“My wife is in travail,” said the Conte. He stood shifting his weight from one leg to the other. His mouth was drawn, his lips compressed into a thin white line.

The brother, Jacopo, hooked a foot around a stool and scraped it over the floor toward him. He flicked his handkerchief over the surface and then sat, balancing one buttock in the air.

The Conte continued to stand. “You must help her.”

Hannah had always found it difficult to refuse aid to anyone, from a wounded bird to a woman in childbirth. “I feel it is a great wrong to decline, sir.” Hannah glanced at the Rabbi. “If the law permitted, I would gladly assist, but as the Rabbi explained, I cannot.”

The Conte’s eyes were blue, cross-hatched with a network of fine lines, but his shoulders were square and his back erect. How different he appeared from the familiar men of the ghetto, pale and stooped from bending over their secondhand clothing, their gemstones, and their Torah.

“My wife has been labouring for two days and two nights. The sheets are soaked with her blood, yet the child will not be born.” He gave a helpless wave of his hand. “I do not know where else to turn.”

His was the face of a man suffering for his wife’s pain; Hannah felt a stab of compassion. Difficult confinements were familiar to her. The hours of pain. The child that presented shoulder first. The child born dead. The mother dying of milk fever.

“I am so sorry, sir. You must love your wife very much to venture into the ghetto to search me out.” “Her screams have driven me from my home. I cannot bear to be there any longer. She pleads for God to end her misery.”

“Many labours end well, even after two days,” Hannah said. “God willing, she will be fine and deliver you a healthy son.”

“It is the natural course of events,” the Rabbi said. “Does not the Book of Genesis say, ‘In pain are we brought forth’?” He turned to Hannah. “I already told him you would refuse, but he insisted on hearing it from your own lips.” He opened his mouth to say more, but the Conte motioned for him to be silent. To Hannah’s surprise, the Rabbi obeyed.

The Conte said, “Women speak of many things among themselves. My wife, Lucia, tells me that although you are young, you are the best midwife in Venice—Christian or Jew. They say you have a way of coaxing stubborn babies out of their mothers’ bellies.”

“Do not believe everything you hear,” Hannah said. “Even a blind chicken finds a few grains of corn now and again.” She looked at his large hands, nervously clasping each other to keep from trembling. “There are Christian midwives just as skilled.”

But he was right. There was no levatrice in Venice who was as gifted as she. The babies emerged quickly and the mothers recovered more speedily when Hannah attended their accouchements. Only the Rabbi understood the reason, and he could be trusted to keep silent, knowing that if anyone discovered her secret she would be branded as a witch and subjected to torture.

“Now from her own lips you have heard,” said the Rabbi. “Let us depart. She cannot help you.” He gave a brief nod to Hannah and turned to leave. “I am sorry to have disturbed you. Go back to sleep.”

Jacopo clapped his hands together as though they were covered with dirt, rose from the stool, and started toward the door. “Let us go, mio fratello.”

But the Conte remained. “I would bear Lucia’s pain myself if it were possible. I would give my blood to replace hers, which as we waste time talking is pooling on the floor of her bedchamber.”

Hannah’s eyes were level with the buttons of his cloak. As he spoke, he swayed from fatigue. She took a step back, afraid he would topple on her.

She lowered her voice and said to the Rabbi in Yiddish, “Is it unthinkable that I go? Although Jewish physicians are forbidden to attend Christian patients, they often do. Christians needing to be purged or bled turn a blind eye to the Pope’s edict. Many Jewish doctors are summoned under the darkness of night and slip past sleeping porters. They say even the Doge himself has a Jewish physician . . .”

“Such tolerance would never extend to a woman,” the Rabbi replied. “If a Christian baby was, God forbid, to die at birth, and a Jewish midwife was attending, she would be blamed. And along with her, the entire ghetto.” The Rabbi turned to the Conte and said, speaking again in Veneziano, “There are many Christian midwives in ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherAnchor Canada

- Publication date2011

- ISBN 10 0385668279

- ISBN 13 9780385668279

- BindingPaperback

- Edition number1

- Number of pages336

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Midwife of Venice

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. 1.15. Seller Inventory # 0385668279-2-1