Items related to Insecure at Last: Losing It in Our Security-Obsessed...

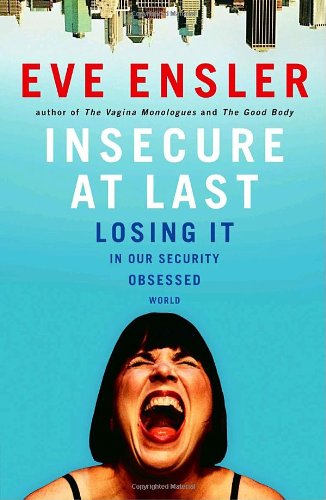

When her stage play The Vagina Monologues became a runaway hit and an international sensation, Eve Ensler emerged as a powerful voice and champion for women everywhere. Now the brilliant playwright gives us her first major work written exclusively for the printed page. Insecure at Last is a timely and urgent look at our security-obsessed world, the drastic measures taken to keep us safe, and how we can truly experience freedom by letting go of the deceptive notion of vigilant “protection.”

Ensler draws on personal experiences and candid interviews with burka-clad women in Afghanistan; female prisoners in upstate New York; survivors at the Superdome after Katrina; and anti-war activist Cindy Sheehan–sharing unforgettable snapshots that chronicle a post-9/11 existence in which hyped obsession for safety and security has undermined our humanity. The us-versus-them mentality, Ensler explains, has closed our minds and hardened our compassionate hearts.

Provocative, illuminating, inspiring, and boldly envisioned, Insecure at Last challenges us to reconsider what it means to be free, to discover that our strength is not born out of that which protects us. Ensler offers us the opportunity to reevaluate our everyday lives, expose our vulnerability, and, in doing so, experience true freedom and fulfillment.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

DRAWN TO WHAT I FEARED THE MOST

THE FIRST MELTING

It is difficult to determine where any journey really begins. From a very young age, I was suspicious of the promise of security. Walt Disney cartoons and Father Knows Best gave me enormous anxiety. I sensed an underworld that was not being expressed, and the absence of it made me nervous. As a teenager I read two books over and over: Hiroshima and Death Be Not Proud. In the first, John Hersey documents individual accounts of those who survived the first nuclear attack. I remember melting flesh, bookcases crushing an older Japanese man, radiation sickness, hair falling out. In the other book, John Gunther’s son gradually and nobly dies of a brain tumor. I do not know which I feared more, nuclear annihilation or a massive tumor in my brain.

I remember when I became afraid of the dark. It was after I watched the movie The Invisible Man on television. There was something about Claude Rains unwrapping his bandages and revealing that underneath there was nothing, he was nothing. I vomited the whole night. I still feel nauseous thinking about it. The idea of becoming nothing, that we were made of nothing, the dissolution of self, of ego, was then my greatest fear. It was my introduction to death.

The possibility of tumors, disappearance, annihilation, circled my childhood, but it wasn’t until I traveled to a war zone in my early thirties that the abstraction of insecurity became a reality. In spite of even my very difficult childhood, I still lived in a comfortable environment. I had a cozy house on a white middle-class street in the USA. There were no air raids. No curfews. There were no bombs dropping around me. There was no one dragging my mother or sister out to be murdered or raped.

Sometime in 1993 I was walking down a street in Manhattan when I was seized by a photograph on the cover of Newsday—six young Bosnian girls who had just been returned from a rape. A rape camp. A place where soldiers held kidnapped women to serve and pleasure them. A rape camp in 1993. It seemed utterly surreal and impossible. Yet the faces of the girls who had survived indicated the seriousness and reality of the situation. There was something about the anger in their faces, and the shock. There was something about the disassociation and the loss. These girls entered me. Or perhaps they already lived inside me. I knew I had to go and be with them. I didn’t really know how or why. I knew I had to go and hear their stories. I had to know the details of what happened to them. I had to be close, to touch them, hear them, smell them, know them.

“They took my sixty-year-old mother and my sixty-eight-year-old father outside. These Chetniks, these boy soldiers who grew up with us, went to primary school with us. They were our neighbors, our close friends. They took my father first and made him stand in the center of our lawn. They were holding guns to his head. Then they casually began to throw stones, big stones, at him, pelting him in his head, his neck, his knees, his groin, as he stood helpless and very confused before us—before me, my mother, our other relatives. He was bruised and bleeding and exposed and they wouldn’t stop.”

I was sitting in a metal chair in a circle of women, all smoking and drinking thick black coffee from tiny cups, in a makeshift doctor’s office in a refugee camp out- side Zagreb, Croatia. I was listening to a thirty-year-old woman “doctress” (as my translator called her) describe her recent nightmare experiences in Bosnia. It was the summer of 1994. I had gone to Croatia for two months to interview Bosnian refugees.

“Then they took my mother and poured gasoline around her feet. For three hours they lit matches and held them as close to the gasoline as they possibly could. My mother turned pure white. It was very cold outside. There was nothing we could do. Three hours they tortured her like this. Then she started screaming. She was so courageous, my mother. She ripped her shirt open and screamed, ‘Go ahead, you Chetniks. Kill me. Kill me. I am not afraid of you, not afraid to die. I am not afraid. Kill me. Kill me.’ ”

The group of refugees around me seemed to have stopped breathing or moving as they listened to this story. Except for their eyes, which filled up or fluttered reflexively from pain.

I heard myself asking reporter-like questions in a strange reporter-like voice, a voice that implied I had seen all this, it wasn’t new, just another war story. I asked questions like “How do you explain your neighbors turning against you like that?” “Did you ever worry about being a Muslim before the war?” I asked these questions from behind this newly developed persona as if it were a secret shield, a point of logic, a place of safety. I was suddenly a “professional.”

“After I had finally escaped and gotten here, I heard our village was safe again. The U.N. raided the concentration camp and my father was released. I began to get a glimmer of hope. Then the real horror happened. The Chetniks invaded my village. They were wild, insane. They butchered every member of my family with machetes. My mother and father were found, their limbs spread out all over our lawn.”

I listened to the doctress’s words and I felt the loss of gravity. Something caved in. Logic. Safety. Order. Ground. I didn’t want to cry. Professionals didn’t cry. Professionals asked questions and transcribed answers. Playwrights see people as characters. She is a doctor character. She is a strong resilient traumatized woman character. I choked back my tears. I bore down on the parts of my body where shakes were leaking out.

During my first ten days in Zagreb, I slept on a couch in the Center for Women War Victims. This was a remarkable place. Originally it had been created to serve Croatian, Muslim, Serbian women refugees who’d been raped in the war. Over three years it had evolved to serve more than five hundred refugee women who had been not only raped but shattered and made homeless by the war.

Most of the women who worked there were refu- gees themselves. They ran support groups, provided emergency aid: food, toiletries, medication, toys, et cetera. They helped women find employment, affordable medical treatment, schools for their children.

In those first ten days, I spent between five and eight hours a day interviewing women refugees in support groups in city centers, desolate refugee camps, and local cafés. I interviewed mothers, widows, grandmothers, lawyers, doctors, professors, farmers, teenagers. I heard stories of atrocities and cruelty. I met a country of women dressed in black: black silk blouses, black cotton skirts, black lycra T-shirts. The courage, community, kindness, and miraculous sense of forgiveness I witnessed on the part of these war victims threw me into moral chaos and deep questioning.

In all these interviews either I was filled with an overwhelming desire to rescue the women or I tried to maintain this “professional playwright” position. I was observing these women as characters, hearing their stories as potential plays, measuring the drama in terms of beats and momentum. This approach made me seem cold, impervious, superior. Both postures were attempts at maintaining a distance and, more important, maintaining my security.

Thousands of journalists had already passed through these women’s lives. They had visited for a day, a week at most. The women felt invaded, robbed, ripped off. The reporters were interested only in the most sensationalistic aspects of these women’s lives—the gang rapes, the rape camps. One journalist had actually sent a fax (these were still the days of faxes) saying, “Get me one raped woman, preferably gang raped, preferably English speaking.” The women had taped the fax to the bulletin board as evidence and a warning.

It was a great honor and privilege that the refugee workers had brought me into the camps, allowed me to be in their most intimate groups. They had even, at times, focused their groups around my being there.

I felt I had not honored my end of the contract. I realized that if I wasn’t “saving” these women—offering solutions—or transforming them into literary substance, I had no idea what to do. My ways of relating were hierarchical, one-sided, based on me perceiving myself as a healer, a problem solver. All of this was based on a desperate and hidden need to control—to protect myself from too much loss, chaos, pain, cruelty, and insanity. My need to analyze, interpret, even create art out of these war atrocities stemmed from my real inability to be with people, to be with their suffering, to listen, to feel, to be lost in the mess.

On the tenth day in Zagreb, a woman who worked at the center generously offered me her apartment for the weekend. I was actually terrified. It would be the first time I’d be alone since my arrival in Croatia, the first time I’d be able to digest the stories and atrocities.

In all my years as an activist—working in desolate shelters for homeless women, tying myself to fences to prevent nuclear war, sleeping in city parks in women’s peace camps with rain and rats, camping on a windy Nevada nuclear-test site in radioactive dust—I had never felt so lonely. I called the States. I reached answering machines in place of loved ones. I paced the little apartment. I tried to read but was unable to concentrate. I lay down on the bed.

My heart was breaking from the inside like an organism giving birth to itself, to the stories of itself: the lit cigarettes almost put through the soldier̵...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherVillard

- Publication date2006

- ISBN 10 1400063345

- ISBN 13 9781400063345

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages224

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.99

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Insecure at Last: Losing It in Our Security-Obsessed World

Book Description Condition: New. Fast Shipping - Safe and secure Mailer. Seller Inventory # 521PY6001V3G

Insecure at Last: Losing It in Our Security-Obsessed World

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. 0.6. Seller Inventory # 1400063345-2-1

Insecure at Last: Losing It in Our Security-Obsessed World

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 0.6. Seller Inventory # 353-1400063345-new

INSECURE AT LAST: LOSING IT IN O

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.6. Seller Inventory # Q-1400063345